In search of a model for understanding war that is compatible with the “War Cycle”.

In what is observed about the “War Cycle”, it must be said that the traditional understanding of wars does not help us much. When it is said that the crisis of 1929 was the cause of the Second World War, it suggests that a war can be reduced to a single cause.

Thus, some might consider the “War Cycle” to be THE cause of wars. This assertion is meaningless. The “War Cycle” is not THE cause of wars but simply a phenomenon that favors wars at certain times. The “War Cycle” exacerbates, amplifies violence to the point that it can degenerate into war, but the war may have been started at the most unlikely times. Moreover, there are times when the phenomenon of the “War Cycle” has almost no effect. We must therefore try to find a model for understanding wars that is consistent with the observations made about the “War Cycle”.

What follows is an attempt to find a satisfactory explanation consistent with what has been observed. It uses several different concepts. It opens up a new understanding of wars.

In order to understand this model of understanding of wars, one must keep in mind two phenomena and their combination:

Phenomenon A – a sinusoidal phenomenon that exacerbates or alleviates tensions

Phenomenon B – an explanation of the outbreak of wars

And finally, the combination of these 2 phenomena

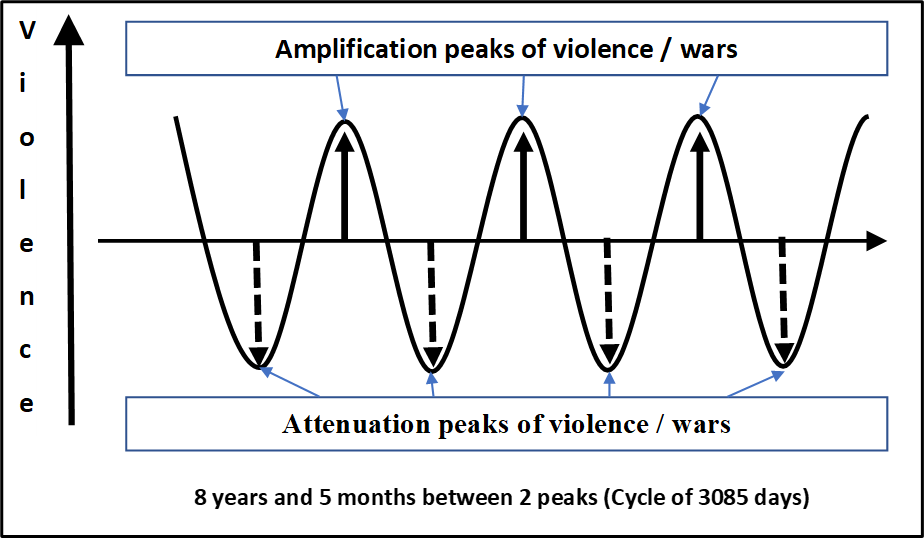

Phenomenon A – The “War Cycle”: a sinusoidal phenomenon that exacerbates or attenuates tensions

There are times when violence is amplified and times when it is mitigated. The transition from one to the other is gradual.

Phenomenon B – An explanation of the outbreak of wars

A war is caused by the accumulation of a set of causes and not by a single cause.

When it is said that the crisis of 1929 was the cause of the Second World War, it would be more normal to say that it was a cause that was added to others such as the Franco-German antagonism of the time, as well as the treaty marking the end of the First World War, perceived as a vexation to be repaired. These are 3 causes that have cumulated. There are still others such as Hitler’s personality. And to all these causes was added this “War Cycle” which appears as a complementary cause. This last cause does not represent more than 20% of all these causes leading to war, but added to the others it may have been enough to trigger this cycle of violence.

Polemology (in the journals of the Institute of Polemology[1] in the 1970s) has distinguished mainly 3 levels of causes:

- Structural causes which correspond to permanent causes (religious, cultural, institutional differences)

- The conjunctural causes which correspond to the succession of events which precede the war without being the immediate cause.

- Indeed, the immediate cause, i.e. the event that is at the origin of the outbreak of the war

The causes accumulate and can become greater than a war triggering threshold[2] .

A war will only be triggered if the accumulation of causes exceeds a threshold called the “war triggering threshold”. This notion of war triggering threshold is considered fundamental. Beyond this threshold, war begins. The accumulation of tensions leads to an incident or action that will mark the beginning of the war.

[1] At that time, the Institute of Polemology was located in the Musée de la Guerre in Paris.

[2] If the different causes of war (structural, conjunctural, immediate) are derived from polemology, the notion of a “war triggering threshold” is specific to the author. There may be other authors who have described the equivalent of a threshold, but they have not been identified to date. If they are ever identified, they will be referenced.

Combination of phenomena A and B on a war amplification peak

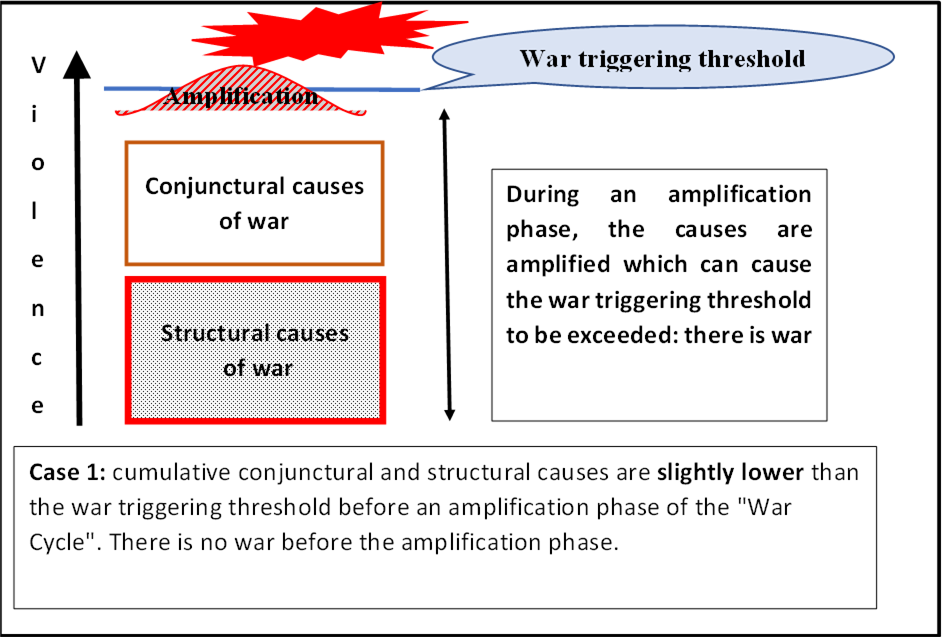

Case 1: Case where the accumulation of causes is slightly lower than the war triggering threshold

In this case, the “cyclical phenomenon”, during a amplification phase, acts as an additional cause that will make the war triggering threshold be exceeded and will thus transform the permanent tension into war.

This explains the choice of the contexts selected and why they allow us to make some predictions.

By looking at recurrent conflicts (e.g. the Arab-Israeli conflict) which always give the impression of being on the brink of war without entering it, we can predict the probable wars in the next amplification phases.

Case 2: Case where the combination of conjectural and structural causes is much lower than the war triggering threshold

In this case, the “cyclical phenomenon”, during an amplification phase, acts as an additional cause, but there is no war because the threshold of war triggering threshold is not reached.

This also allows us to imagine means of action, i.e. to act on the identified causes to avoid crossing the war triggering threshold. Not knowing the origin of the cyclic phenomenon, we cannot act on this cause. Only the known causes can be mitigated. Classic and vigorous negotiations should reduce tensions and the causes of war. If they are carried out before the next amplification phase, we can hope to avoid a war that is considered probable, since even with the amplification caused by the “cyclical phenomenon” the war triggering threshold will not be reached.

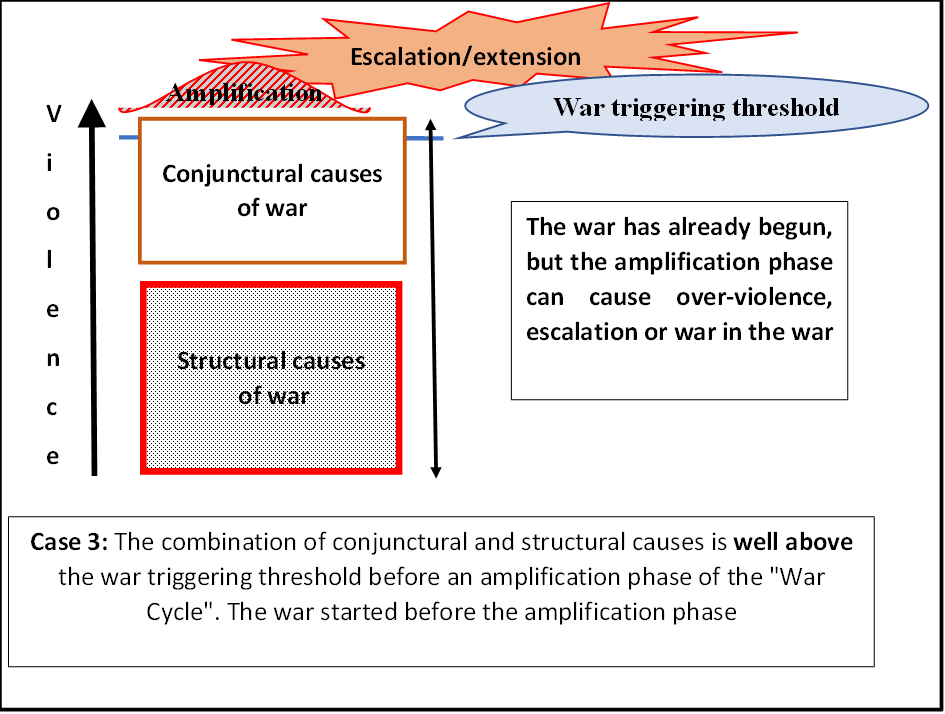

Case 3: Case where the accumulation of causes is well above the threshold of war triggering, even before the amplification phase

In this case, there is already a war before the amplification phase. There is no new war since it has already begun. The period of amplification can lead to visible “over-violence” through military escalation (local, regional, international) or new violence. Several examples illustrate this case:

- In early 1964, the bombings in Vietnam marked a military escalation at the amplification phase. The war had officially been going on for some time, but the real escalation occurred at this amplification phase.

- The war in Iraq began in 2003, at the time of a mitigation peak, the American victory was followed by an Iraqi civil war which coincides well with the amplification phase. This internal Iraqi violence increased up to the war amplification peak and then steadily decreased, until it gradually resumed with the next amplification phase and the war against the Islamic State.

- The war in Syria began in 2011 during a mitigation phase, there was an escalation and internationalization of the war that began in 2014, during the amplification phase, and continued in 2015 and 2016 before the Islamic State’s pushback began. This escalation of the conflict from 2014 to 2016 corresponded to an amplification phase of the “War Cycle.”

It is important to understand that this model and these 3 identified combinations allow us to better understand the effect of this “War Cycle” which can be visible in different ways:

- the outbreak of a new war (Case 1)

- the escalation or extension of the war in a wider area (Case 3)

What should be done to complete this embryonic explanation of the wars?

Only a few concepts were posed. They explain that the cyclical phenomenon is only one cause among others.

To go further, it would be necessary to quantify the causes of wars in order to transform these concepts into something measurable. This is another reflection that should be carried out and which is not addressed here.

The principles set out here allow us to understand that in some cases the “War Cycle” can provoke wars, in other cases it can provoke none at all, or it can provoke an escalation or extension of an already existing war. These principles cling to more classical concepts of understanding war. The “War Cycle” does not question these explanations but completes them by identifying an additional cause that was, until now, invisible and which is added to those that already exist.

This model of understanding wars is consistent with what is observed. The “War Cycle” does not systematically produce a war, but indicates the conditions under which it can promote war or escalation.

This explanation also breaks the fatalism that some might see in it and allows us to understand that the predictions of possible wars will first be based on a classic method of war analysis, before identifying conflicts that could degenerate into war.

updated on April 4, 2023